BONE THUGS

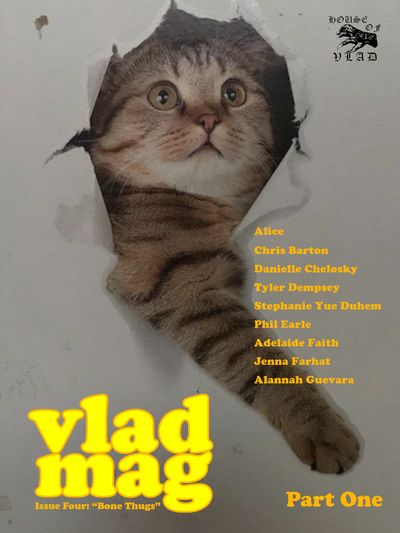

VLAD MAG #4 (PART oNE): “BONE THUGS”

A HOUSE OF VLAD PRODUCTION

© 2024 by House of Vlad Press

All rights reserved. No part of this content may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, with the exception of excerpts used for critical essays and reviews.

These are mostly works of fiction. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Release Date: May 3, 2024

Guest Editor: Troy James Weaver

Cover design: Percy Hearst

Cover photo taken by Andrew Chadwick of a painting by an unknown artist

Author photos © the authors

Founder and editor: Brian Alan Ellis

Contributors: Alice, Chris Barton, Danielle Chelosky, Tyler Dempsey, Stephanie Yue Duhem, Phil Earle, Adelaide Faith, Jenna Farhat, Alannah Guevara

Thanks for reading.

HOUSEOFVLADPRESS.COM

Alice

LET THESE SENTENCES HAPPEN TO YOU

My cat died, and I started watching the same plateau truther video over and over. This Russian guy thought plateaus were giant tree stumps. The Devil’s Tower has cells, he said. Hexagonal, like cellulose. The woman who dubbed his video over in English kept pronouncing it hex-ogg-onal. Hex-ogg-onal.

Every sentence of this video got more unhinged. Arizona is named that because it was the zone of the Aryans. Fossils are actually remains of a time when life was silicon-based. I let these sentences happen to me. Only life can construct regular geometric shapes. 300 ∑ 20 is an equation, and the answer is 6000. We invented the nuclear bomb in the 1840s, and the whole world covered it up. Prehistoric trees reached the lower atmosphere. Prehistoric giants cut those trees down with enormous prehistoric saws.

It was like being power washed. You sat there and you waited. Nothing you could do about it. It hurt so good. But hex-ogg-onal was a paper cut. Nothing you could do about that either, but you couldn’t stop trying.

My cat was the tamest animal I’d ever met. He slept on my face at night. Used my cheek as a chin rest. I was so desperate to keep him alive I spent all my savings. He lived pretty long, for a cat. But then he died, and I started watching conspiracy videos.

What else was I gonna do? My college friends had teenagers. My sister was backpacking through Malaysia. My mom, who I hadn’t spoken to since my 20s, was on dialysis.

Jilly called me from work. Well, from where I worked before quitting to watch conspiracy videos. She said, This place sucks without you, and I was like, Jillian, stop trying to hit on me. I know you’re not into vagina. Yeah, but you sometimes are, she said. Sometimes, I said. Not yours. How ’bout you instead come over and help me eat the carton of year-old mint chocolate chip ice cream in my freezer, which probably tastes like freezer. Maybe later this week, she said.

The plateau truthers are an offshoot of flat earth guys. Even flat earth guys think they’re weird. But there was an audience for this, clearly. The comments under the video are awed, thankful. I felt like replying HEXAGONAL IS NOT PRONOUNCED THAT WAY to every one of them, but at least four Presidents have said nuke-you-lar and nobody impeached them for it. If you know you know better, it doesn’t fucking help unless everyone else knows you know better, too. So, hex-ogg-onal was like a splinter under a fingernail. The smallest fucking problem with the video was the one preventing me from enjoying my brainwash.

By the time Jilly came over I was thinking about killing myself. Like not in a dramatic way. I just think the human mind isn’t designed to have no purpose at all. Plateau guy and hex-ogg-onal woman had nothing but purpose. I could unlatch my brain and borrow their purpose for an hour, but it wasn’t perfect thanks to the mispronounced word, and I still had to land in my own fucking brain afterwards.

I thought I’d probably drive my car off the side of the road, or something. I was gonna do it that Friday, get hammered and take hairpins until I overshot. But Friday, Jilly dropped by, and we were eating that nasty freezer-burned tub of ice cream outside under the porch light because it was a hot night when she said, That’d be a great tree for a birdhouse.

Which one? I said. That big one, she said, over there. The live oak. You can hang birdhouses without hurting the tree. Oh yeah? I said. Yeah sure, she said. Google it. You still have your dad’s old carpentry tools in the garage, right? Sure, I said. So, make a birdhouse, she said. I took a big scoop of nasty ice cream. For what? I said. What kind of bird? She shrugged and said, For whatever comes.

ALICE is a pseudonymous nonbinary femme writer, editor and painter from Houston and London. Aer fiction has appeared in X-R-A-Y, HAD, Hobart, and Rejection Letters, and was reprinted in Best British Short Stories (Salt Publishing, 2022). Ae are founding editor of bodyfluids.org.

Chris Barton

WORMS LIKE NAPALM

I ate mushrooms and went to a Botanical Garden to watch the sunset on a Sunday afternoon.

The sunset wasn’t exciting, so Hana and I decided to walk around while there was still light out.

The month was November, but it felt like early April.

Only everything was dying.

Brown leaves and cool winds on an otherwise sixty-degree part of the world.

Birds chirped and flew around everywhere—a lot of birds.

“Around a thousand,” Hana guessed.

The birds congregated in trees and would fly up suddenly in an intense harmonic flutter, and for a minute afterward, everything was still and silent.

We walked to a giant orange lawn chair and sat down to look at the skyline.

It was the kind of lawn chair that people take photos in while on road trips—one where the chair is empty and another where they’re sitting in it.

We sat in the lawn chair and Hana put her legs over my legs and we watched birds fly and recorded videos on our phones.

The birds would swoop in different groups, then twist and circle around the sky, creating a large helix, and some of the groups would turn and mesh into each other and then separate again.

It was uniquely lovely.

Much better than a sunset.

Hana and I swallowed two pinches of mushrooms, then chewed peppermint gum.

The flavor of the gum was Perfect Peppermint.

It was pretty good.

It started to get dark, so Hana and I walked into the garden, where there were little animal gnomes.

I opened the wooden gate and made eye contact with a sheep.

And the whole world felt like a B-movie about a lost sheep that no one would ever watch.

We walked to a cluster of pine trees where all the birds were and listened to them hop and flutter, and I thought about a less disturbed time with more trees and more birds when humans slept on the ground in the middle of all the bird sounds.

And I felt a little frightened, imagining it was me.

And I felt a little like shit.

We walked back to the parking lot, and I drove home in a large truck that seemed to be growing larger.

I drove slow and felt light and good, and laughed while Hana gave directions.

The fast-food lights’ glow shone into the cab, and everything looked like anime.

We drove to my apartment and made ginger tea with honey and lemon.

Then Hana put whiskey in the tea, and everything was warm and glowy like a fast-food sign.

After we finished the tea, I opened two Modelo bottles, and we drank quickly while my cat ran his paw under the stove, trying to catch a mouse.

Another mouse came out from the top of the stove and ran along the baseboard of the kitchen counter, looking for food.

Except there was no food.

Hana said the mouse stole half of a piece of cake from a cutting board two days ago.

Banana bread cake leftover from Thanksgiving.

She said she set the piece down on the cutting board and was eating the other half at the table when she looked up and saw the mouse run out from beneath the temperature dial on the stove and grab the cake.

I drank my Modelo and watched the mouse run back and forth behind the coffee maker on the counter.

“Fuck, he’s fast,” said Hana.

“Slow down, mouse!” I yelled.

Then we took turns jumping and screaming at the mouse.

My cat’s eyes widened, and he looked up at us from his side, lying on the floor.

Eventually, the cat got bored again and ran his paw under the stove.

I felt warm and glowy from the mushrooms, like a fast-food sign that had just flicked on.

Hana opened two more Modelo bottles.

The mouse was gone.

I went outside to smoke a cigarette, and my friend followed.

It was cold now–double jackets cold.

I smoked and felt less glowy, but still nice.

My cat scratched the inside of the door.

I opened the door, and my cat ran away fast and down the street.

“He does that,” I said.

November cold, familiar like an album you listened to in high school but never listen to now.

I looked at the breath clouds Hana and I made that hovered above us, then watched them drift and tear apart.

I looked at Hana and thought about all the times we stole food from the hot bar of a grocery store when neither of us had a car.

Then I thought about college, whether I should’ve gone or should go back.

Then I thought about cockroaches and how they hold their breath for forty minutes but can only live a few days without water.

Then my roommate’s car pulled into the driveway.

“How was work?” I asked.

“I carefully added seven extra cups of ranch dressing to a to-go order for a customer named Nada,” said my roommate. “As per her request.”

“I feel filthy now,” said Hana.

“We are all filth personified!” said my roommate.

My roommate grabbed a six-pack of Coors from the backseat of his car and handed us both a beer.

Then we all went inside and sat on the couch.

We played a video game called Worms.

Each person plays as a different team of earthworms and takes turns attacking other earthworms with various weapons.

The worms are different sizes.

The small worms are fast but die easily, and the big worms are slow and can barely jump but can take a lot of damage.

The game is nice because you destroy the landscape while you play, and I guess that’s why we liked it so much—the challenge of hanging on and finding glory in what was left.

Like a forest that loses its leaves, but birds still sing in it.

Half of a piece of stolen banana bread.

An uninteresting sunset.

Land mines.

Floods.

Bazookas.

Holy hand grenades.

Dynamite.

Mortar strikes.

Like napalm.

CHRIS BARTON wrote A Finely Calibrated Apocalypse (Bottlecap Press, 2024). His writing has been featured in Peach Magazine, Hotel, Hobart, The Plenitudes, and elsewhere. He lives in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Danielle Chelosky

MY GIRLS

Pink-tinged rays of sunlight poured through my blinds. The rosy vibrance swept me into a placid haze and floated me toward a blissful void. It was the last day of a heatwave I thought would never end; I preferred tripping on LSD over drinking water. I knew this poetic period would expire, but I didn’t think it would be so abruptly, so violently, the piercing ring of my mom’s phone snapping me out of my mirage. I blinked and all the magic was gone.

My mom was silent for a while. I tried to recapture my citrusy existence, to resuscitate the delicious lingering feeling. Sam and I immersed ourselves in the hallucinogen for a week and I was in its afterlife. On my wall, in between an old Joy Division poster and a photograph by Nan Goldin, the purple paint was chipped in the size of a half-heart. The curves moved with a swift slenderness, like it had been carefully carved, done masterfully with the sharp point of a sculpting tool. The knife’s edge could even be just slightly rounded, and it would still dig into the wall just the right amount. I thought of the number of times I accidentally stabbed myself with a linoleum cutter making prints. No matter the blade, the metal tip was always unforgiving, a bloodbath in the palm of my hand. I liked to make prints sometimes; the supplies were easy to acquire since I worked at Michael’s. First, I would make a sketch. It could be of someone’s face, or an elaborate pattern, or an inspiring landscape. Next, I put the linoleum under the paper to draw an outline with a marker, so that the sketch is transferred onto the linoleum. Then, I’d chip away at the linoleum—this was the gory part—until the sketch was fully carved. I’d splatter black ink onto my wooden slab and roll a brayer over it until the entire surface was covered. Finally, the linoleum carving would be pressed against the black ink and then stamped onto a piece of paper. You could also use other colors as well, but I preferred the simplicity of black.

Footsteps approached my room in faint echoes, and I felt as if I was in a sleep paralysis dream. I eyed the half-heart, which could’ve been an ear, or maybe the outline of a swan. I reached out to touch it, to rest my thumb on the lacuna, to press my skin against it so I would be marked with an indentation. But before my fingertip met the wall, the door opened.

“He’s dead,” she said. My finger lingered in the air like that, like I’d been caught. Her face was blank, like she’d just informed me about a work event she had to attend or a cousin visiting from college. She turned around and went back to her bedroom like she’d never approached me at all. I contemplated that she was just an apparition. Maybe I was still asleep. But then I did it—I touched the shape, and it hugged the small of my fingertip. I closed my eyes and returned to my first memory of my dad: He smoked a cigarette with one hand and held my small fingers with the other. The sun was blinding, and I was at that age where everything was ephemeral and barely real. He was walking us toward somewhere brighter, but I couldn’t remember what it was. I scrunched up my face, as if that would help my memory, and rummaged through my head, desperate for a destination. It was like an overexposed photograph. When I let go and opened my eyes, tears dripped off my chin.

*

It was the summer of 2009. I was seventeen, and the grip of Phoenix’s Wolfgang Amadeus Phoenix, released earlier that year, was tighter than ever in Lancaster, which is really more of a town than it is a city. My grief was soundtracked by the ubiquitous anthem “1901.” All music was like this—effervescent, eccentric, and packed with melodies you’re worried might never leave your head. Or at least that’s all my milieu was blaring.

Sam played it directly into my ears from her iPod, planting headphones over my head in the basement of the funeral home, twirling the wire in her fingers while I fell in and out of stoned reveries. I thought about the way death makes the living people rush—take the body, put it in a casket, make it look presentable. I flinched at the idea of a woman dabbing my dad’s cheeks with blush. I imagined him resurrecting just to slap the makeup out of her hands and yell that he was a man.

How would I get through three days of wakes? It struck me as a strange stretch of time, especially one to be spent socializing over sadness, kneeling before a coffin that held a human who had become an object, a corpse like a container for failed organs. We could not see him; it was a closed casket, considering the violence of his death, the way the destruction had been painted onto his face. The carpeted floor downstairs possessed a bleak black-and-brown pattern, like a boring arcade. I remembered inhabiting this same space as a kid when my grandfather died. I was all smiles and laughter, opening every door, thinking a new world may lie behind it. Now I knew that every door led to nowhere.

“Isn’t it so good?” she said, breaking me out of my daze. Reality was far away, hidden behind a wall of tragedy. Tragedy always makes you feel like you should be doing something other than what you’re doing. You’re just never sure what it is.

The fuzzy synthesizers and buoyant rhythm imbued me with an urge to laugh like I was a kid again. That’s what the song felt like—being young, free of the weight of knowledge and experience. I wanted that sense of wonder again. But if I let the laughter rise up in my throat, I feared something else would come out—like a sob or vomit.

I nodded. “It’s fun.”

“Peter showed me it,” she said, blushing. Peter was a student at F&M, the local liberal arts school whose parties we crashed so often they assumed we were enrolled there. They passed down their vices to us like hipster heirlooms: hot websites like Myspace, whose sliver of danger was enough to give us a thrill from the safety of our homes; cool music, like the indie iconoclasts Panda Bear, or classic cult bands like The Fall; and, of course, any drug that was shoved in the tiny pink children’s jewelry box in their drawer, ranging from weed to LSD, depending on how generous they were feeling and how much charm we felt like mustering up for these miscreant mentors. A guy in skinny jeans and a Sonic Youth T-shirt once handed me a copy of The Myth of Sisyphus. I used it as a coaster.

Sam folded up her headphones and slid them into her bag. She cleared her throat and said, “Do you think any hot guys are coming?”

I paused. “Here?” I asked.

She nodded.

I rolled my eyes and planted gum onto my tongue. “Gonna go with no for that one,” I said, chewing so I could have something to occupy myself with. I hated the stillness of everything.

She took the pack from my hands and pulled out a strip for herself. “Let’s stand outside and look all mysterious,” she proposed. “We’re too cute to be hiding. These outfits are being wasted.”

We both donned black dresses. Hers stopped right above her knees, showing off her spotless legs, glowing in the artificial funeral home light. Makeup amplified the subtle features of her face—eyeliner to make her blue irises pop, bright red lipstick forcing anyone around her to focus on her mouth—like she was the one going in the casket to be admired. My dress flowed to my ankles, silk like lingerie. I never learned how to do makeup—there was nothing on my face I wanted to accentuate. If anything, I wanted everything to be understated, underwhelming. I wanted to be seen as a ghost.

“OK, you’re being too weird,” she said, bringing me back to earth again. “Can we at least go upstairs before you space out again? I’m gonna lose my mind. It’s like I’m talking to a wall.”

Pale figures cloaked in dark clothing clustered so that you’d have to put a hand on a shoulder to sneak through, not without the gliding of fabric. From outside the crowd, I scanned faces: an aunt distraught, an uncle drunk, a cousin unbothered and maybe stoned like me. Tears, smiles, and blank expressions speckled the throng. The smiles were sad smiles—the kind with heavy eyes.

Everyone appeared to me as actors in roles, picking their way of pretending. I couldn’t imagine sincere sobbing; I could never cry in public because I would never want to draw that much attention to my own vulnerability. If I was being watched, I wanted to be the one with power.

Before I could even consider approaching the swarm, the distraught aunt swept me into the tide, taking my face in her hands. “Oh, honey,” her nasally voice uttered, like she was in physical pain. “I hope you’re doing OK. He loved you so, so much.” Her palms sent a cold shock through my cheeks, as if she were holding ice cubes beforehand, or like she was dead, too.

“Thank you,” I said, my minty breath in her face, which then crumpled up like a piece of paper to be thrown out. The wrinkles in her forehead stared at me like living things. I could see the flakes of her skin. Death was everywhere.

Finally, she let me go and pulled me into a hug instead, which was more bearable. Embraces are less confrontational—it lets the warmth of bodies do the talking, and her fur coat was momentarily comforting. I didn’t have to look at anyone or anything; I could finally close my eyes. Then, she wandered over to the casket, setting her manicured hand on the mahogany.

“You good?” Sam asked.

I sighed. “I need a drink.”

Outside, men gathered, sipping on flasks and smoking cigarettes. Bleak sincerity abounded. They didn’t feel the need to put on a show; without their wives, they could say whatever they wanted, behave however they wanted. Sam smiled mischievously at the sight, even though they were all mostly ugly and old, deteriorating before our very eyes. They were either bald or fat, except for Jonathan, my dad’s best friend who was about a decade younger than him. At a repair shop, they worked on cars. I would visit as a kid, prancing through the connected convenience store collecting candy in my palm and eating it before anyone could see. Jonathan, in his deep blue jumpsuit, would take me in his gloved hands and joke about arresting me. And then he’d let me do it again and again, keeping my secret.

He was in the middle of talking as we came out through the door. “A lifetime working on cars,” he said, “just to end up being killed in one.”

“He made it longer than he should’ve,” Uncle Teddy said, his harsh words being met with a disgruntled choir. “No, no, I mean, remember when he crashed that Bronco? The way it sent the other car flying into the guard rail, the poor Honda almost falling into the lake.”

I’d heard this story before, only in whispers from Jonathan. He made me promise not to say anything to my mom. She wanted to seal up my dad’s past in an empty bottle and toss it into the ocean. The more secretive she was, the more curious I became. This anecdote was a favorite of mine—I pictured the vehicle dangling above water, all from the force of my dad’s foot on the gas. He always drove with fierceness, not to be confused with recklessness. He was meticulous in his pursuit of danger.

Jonathan smiled at me genuinely, though the eyes twinkled with pain. “Hi, darling,” he said to me, putting one arm around me and squeezing. “How are you holding up?”

I shrugged and reached for his flask. He chuckled. “You really are your father’s daughter,” he said. Sam blew a pink bubble until it popped, the crackle rippling through the air. Sam spit her gum onto the pavement, and I did the same.

“Bourbon is not for ladies,” my Uncle Ernest said.

Jonathan shook his head. “This isn’t the 1950s, Ernie,” Jonathan said. “Women can do things.”

Uncle Ernest, bald and fat, sighed like he was just finding this out. The men all started talking amongst themselves again. Jonathan turned to me and discreetly held out the flask, the metal glimmering under the hem of his suit jacket. I took a swig, and the liquid was warm and sweet in my mouth like tea with honey. Sam beamed, reaching out her hand. I looked at Jonathan, and he gave me a shrug like, Why the hell not? She brought it to her lips and left a red stain.

Jonathan was tall, sort of lanky, with kind eyes and brown curls. He looked like a perpetual boy. When Sam and I saw Forgetting Sarah Marshall in the theaters, we squealed, making jokes about Paul Rudd’s resemblance to him. But he does not have the same childlike aura as the actor; he has a vaguely solemn air, one of adulthood and disturbance.

“Where’s your wife?” Sam asked him, handing the flask back.

“Couldn’t take off work,” he said.

Miranda was an undeniably stunning woman. The two made a hot couple. At six-foot-two, Jonathan towered over everyone, but especially his five-foot-five wife. Her hair was similarly chocolatey, but it cascaded with a consistent straightness, never even a wave or a knot. She looked haunted sometimes, like if you sifted through the wall of dark strands, you might get lost.

I knew Jonathan was a wreck after what happened to my dad. The only thing protecting him was male integrity and bourbon. I knew men weren’t allowed to show emotions, but I overheard my mom divulge on the phone that he’d quit his job at the repair shop because he didn’t want to be there without my dad. He didn’t want to work on cars at all anymore. My dad served as a kind of mentor to him. Jonathan became lost like a kid. He looked it, too, his eyes wandering around this group of deteriorating men, often drifting to the parking lot to space out, black pavement contrasting the whiteness of the sky. A rare sunless summer day, a slight breeze creating a chill and previewing the forthcoming fall, after that disorienting heatwave.

Sam frowned. “That’s a shame,” she said. “Who wouldn’t want to miss this?”

The men all flocked back inside, the stench of cigarette smoke, cheap whiskey, and fragile egos fading away just like that. For a second, I felt young, and then I remembered who I was. “This year is gonna fucking suck,” I blurted, not to Sam but to the empty sky.

“No,” Sam said. “Absolutely not. I know this is your dad’s wake and whatever, but I will not allow this attitude for our goddamn senior year of high school. This is what we’ve been waiting for.”

We had the whole month until the semester began, yet I felt it slipping through my fingers like sand.

Would everything slip through my fingers? First summer ending, then high school, what would things be like then? Who would I be? I wanted to know my future, yet I didn’t even know my present. It was scattered like an undone puzzle.

Sam nudged my shoulder, reminding me I was alive. “Quit that,” she said about my tendency to space out, to meander around the ether in the middle of a conversation. If it weren’t for her, I would’ve gotten lost a long time ago. “You’ll be fine.” She took my hands in hers. Suddenly, the sun peeked out from behind clouds. A holy yellow poured over everything, like the earth was waking up. A choir of cars honked, and birds whirred by in a triangular formation. “Also,” she continued, “do you have any cute cousins?”

“Enough,” I muttered begrudgingly but with a vague smile. “This is a time for death, not sex.”

“They’re like the same thing,” she said. “I don’t know. That’s what Peter told me. He really loves this philosopher called Georges Bataille that has a book about that. Sounds interesting.”

“Sounds like he’s gonna murder you,” I said.

“Ugh,” she recoiled. “Can you make sure they make a movie about me, and not just a Dateline episode, but, like, a whole production?”

“Who do you want me to get to play you?” I asked.

She thought for a moment and then her eye twinkled. “Megan Fox,” she said. It was not even a narcissistic answer; she looked like a younger version of the beloved actress, with black hair that glimmered even when there was no light and eyes that could easily intimidate when squinted just the right amount. She wore tops that complemented her push-up bras, taking advantage of the quick development of her eighteen-year-old body. Men were often glaring at her and then looking away once they recognized her virile nature, as if her flirts were a hiss instead of a mating call.

“Speaking of,” she added, “we have to see Jennifer’s Body when it comes out. She looks so fucking hot in the trailer.”

“Let’s get drunk at the cinema,” I suggested.

“Deal.”

*

The days designed for grief stretched out, like a worn childhood sweater. Time wasn’t the same within the walls of the funeral parlor. It was like a waiting room. The monotonous nature of everything—small talk, beige walls, the lingering of awkward bodies—drew out the minutes until they felt like hours. It was an inverted mirror of the week before, when Sam and I structured our schedule around LSD, letting the substance temporarily warp the clock with its color and radiance. It seemed those days belonged to another lifetime. A clear before and after splitting my life in two. In the days leading up to his death, the summer afternoons were a soft pink, my psychedelic trip making me float like an iridescent, gentle bubble. In an instant, it popped, and everything turned grey.

More relatives and family friends took my face in their hands like it was an object to be held. I felt tainted by the end of it, different fingertips morphing the skin of my face, filling my pores with germs. It was an overwhelming amount of touch. Sometimes, if I was lucky, it was just my shoulder, or my hand. But I resented the way grief seemed to obliterate boundaries—the person in mourning instantly becoming accessible to anyone. Shouldn’t it be the opposite? I’d prefer to go into hiding, no questions asked.

The funeral was an anticlimactic finale. It was a sweltering day when we cramped into the pews for the service, like the heatwave never left. It was the church I’d attended since I was a child, yet it felt unfamiliar. Anxiety makes every space you inhabit feel like a floating orb. The stained-glass windows burst with vibrant color, juxtaposing the dark mahogany of everything else. It was so brown it was like we were the ones buried in dirt. Hands waved at faces, desperate for a reprieve from the humidity. A priest talked and talked and talked and my eyelids drooped like I was in history class all over again and I was about to get in trouble for not paying attention. I’d mastered the art of tuning out sermons. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have made it through my childhood. I breathed shakily when, after all the rambling, the coffin was carried. I pictured my dad rattling around in it like an item in a box being shipped in the mail. At least he doesn’t have to suffer this heat, I thought.

More words were spoken by the priest at the cemetery, his voice big in the empty air. I tuned it out again because I knew he reiterated the same clichés at all these things. He was loved. He would continue on in our hearts. He would finally reunite with his father. I wondered if the sentiments lost their meaning as they were uttered more and more, and if they just gradually became untrue. Planes flew overhead as they always do—people always have somewhere to go, though it seemed I never did. I wished someone would tell me what to do.

Wrists flung, flowers cast, a game of commemoration. Sam won, the rose landing on top of the wooden cover. Sam held my hand as they lowered him into the ground, his coffin going right next to his dad’s.

There’s the part when the funeral is over, but you don’t know what’s next. Technically, you do. You have plans to get dinner even though it’s still pretty early and you’ll probably get inappropriately drunk at the restaurant because this is one of the few situations where that’s somewhat appropriate. Because then you really don’t know what’s next, you just go home and wait for whatever it is you’re supposed to feel.

Moving through life is a lot easier when intoxication is the destination. Sam and I giggled, kicking each other under the table of this Italian place where the bread was never-ending and erotic, butter as sweet and galvanizing as bourbon in our mouths. We were wine drunk—the only drunk we were permitted by Jonathan, who handed us glasses and said, “If anyone asks, you’re twenty-one.”

For a moment, it was like we only sat at this table for pleasure. A steak sizzled on the plate in front of me, with a bowl of chicken fettuccine Alfredo beside it, creamy and thick; Sam was devouring a tuna melt, alongside a mountain of pesto; elsewhere, I spotted an assemblage of radiant clams, fried calamari that crunched as you bit into it, a pile of mussels, and Uncle Ernie was even eating a lobster tail, dipping the soft, pink fluff into butter.

My mom was a reminder of the reason we were there. She burrowed into bottles of vodka, sequestering into a corner of the table where the only person she allowed to speak to her was Jonathan. Everyone’s inebriation allowed them to act like everything was jolly. Hers was evidently not the same. I felt embarrassed. I watched as Jonathan put a hand on her shoulder and spoke softly. He had a delicacy to him that separated him from other men. She put her head on his shoulder. It looked almost like a holy image; my mom was looking for solace, and Jonathan was a saint providing it. Sunlight wafted in through the window behind him, the yellow rays shrouding around his head like a halo. Meanwhile, my mom was in the darkness of his shadow, the bags under her eyes heavy and grey.

All the men were bursting with laughter, keeping the energy high. Their voices echoed through the restaurant as they reminisced mischievously, sharing stories of my dad that went back as far as twenty years ago. I wondered how he could’ve been at a job that long, especially a job so tedious. Whenever I’d see his hands, they were tinted black from all the work, of being on the ground to dissect vehicles, operating on them like a surgeon does with a human body.

Sam slammed her hand down on the red tablecloth. “I know this sucks,” she began, and I was instantly startled by her seriousness, “but we should have more extravagant dinners like this. Why does someone have to die for us to indulge?”

I actually agreed. I smiled and raised my glass, nearly spilling it. “Here’s to hedonism, constantly and forever.”

“Cheers,” she said, and we clinked our glasses.

DANIELLE CHELOSKY is a music writer at Stereogum, an editor at Hobart, and an editorial assistant at Amphetamine Sulphate. Her book, Pregaming Grief, was published by Short Flight/Long Drive in 2024.

Tyler Dempsey

STUPID POEM

This is a stupid poem—doesn’t rhyme, have line breaks, come on. In it, I’m in Hawaii. That’s poetic. Show me something in nature resembling a stupid poem more than the Banyan tree. I’m waiting. Remembering living with Jeff Bridges from The Men Who Stare at Goats. Not Jeff Bridges Jeff Bridges—the guy he was pretending to be. Jim. Jim liked me. Said, “I can give you work.” He said, “You can stay on property.” He didn’t mention one of the many rooms on property. Just “on property.” On property at large. So, I “lived” in 8 feet of culvert sitting on the ground. That’s what makes this poem stupid. I mean, a culvert? Come on. I named it “The Pill Bug.” Cause of all the bugs. I was in my twenties. In Hawaii. Life couldn’t get better. Each morning I’d wake up and walk around. Jim would be trying to kill a goat by staring at it and other twenty-somethings who lived on property would be showing off their bodies, cooking vegan food, falling out of coconut trees, etc. Sometimes I’d walk six miles in sandals just to read a book in the park. A poetry book. That’s some poetic shit there. Think you’re good at picking up ladies? Well, I picked one up and lived in a fucking culvert. How ’bout that? I picked up this woman that time I lived in Hawaii. If it makes you feel better, she was married. Or “engaged.” Not engaged enough, because we had sex in my fucking culvert. Dirty, bug-infested sex. The next morning, another twenty-something asked while eating vegan food who’d had company last night. “Nice,” he said, when I raised my hand. Me and the nearly married woman had sex again in a field beside a bunch of cattle. I mentioned someone heard us that first time in “The Pill Bug.” She thought the field was “safer.” Remember the guy who said, “Nice”? Well, a few weeks later he kept me up all night. Laughing the way cartoons characters do when they’re batshit crazy. Nice, I thought. Figuring he’d taken mushrooms. That that’s what kept me up, all the good times he was having in his head. Yin, yang, I thought. Karma. He was taken off the property the following morning, though. Turns out, it wasn’t mushrooms but mental illness that had him cackling like a mad hatter. He was batshit crazy. Another time a friend hurt his foot and was sad and couldn’t work. The friend was scared, because people who can’t work don’t exactly have a long shelf-life in Hawaii. He was scared he’d have to limp back to Kentucky or Minnesota or whatever non-poetic place he was from and go back to being a normal person. Convinced, if that happened, no one, especially himself, would ever love him. I told him I’d fix the foot. “Lie down,” I said. “On the ground.” I sort of massaged the foot. Like I knew what I was doing. Mentally projecting all this love into that part of his body. When it was done, he said, “Yeah, that does feel better.” Nothing can last, especially a poem, so my time in Hawaii was over. Poof. Me and the not-yet-married woman had sex one last time. Our flights ended up in the same city in California before zipping us back to real life. We had it in the shower. Which, being so much cleaner and more private than “The Pill Bug” or that field, you’d figure would be the best sex we had. But it was listless. Without heart or any magic. Because there was no more poetry in our story. Poof. She flew back. Married that guy. I hope she’s happy. And that friend, he emailed months—years—later. Said, “Hey, you really fixed my foot, I can’t thank you enough.” He said, “I felt like I should tell you, I had sex with…” then he typed the name of the not-married woman. Right in the email. “Sorry,” he said. Sometimes I get to thinking. About Jim. The woman and the mad hatter. The friend with the foot and all the other unbelievable people I’ve met. How none of it makes sense and then it’s gone. How life, if you stop and think about it, is like a stupid poem. But I hardly ever think about it.

TYLER DEMPSEY wrote three books and hosts Another Fucking Writing Podcast. He lives in Utah with his dog.

Stephanie Yue Duhem

REINCARNATION IS ALSO A GENERATIVE PRE-TRAINED TRANSFORMER (GPT)

A number of phrases in this poem originated from interactions with a GPT-based tool.

The nautiloid cities of my mother’s womb,

where voices are mind-sound,

give on a red-tinted sea

with a blackness beyond it.

Days pass, and decades,

like pennies from the same mint.

I notice my face

stamped over and over them.

How many times has it been?

The School of Medicine

confirms I am being

re-recorded live, though

the staff are loosing

doves among rafters, distracted,

brows gleaming

like heirloom compasses.

Then: a noise of gloves thrown,

wet from the wash, across chairs.

In the room: a few rags of fur,

a prism, a doll

made of pills,

rows of insects pinned to newspapers,

and recondite conches.

What smallnesses I chose

when I was conscious.

STEPHANIE YUE DUHEM’s debut poetry collection, Cataclysm Moves Me I Regret to Say, will be published by House of Vlad Press in 2025. She lives in Austin, Texas.

Phil Earle

DOCTOR CHAINSAW

I went to a doctor by Prospect Park. There was a tiny waiting room; a couch covered with plastic, an air conditioner humming hard in the window. All the magazines were expired. A plastic mat covered the floor. I thought maybe they were going to take me apart with a chainsaw. My headaches were evolving. At first it was a tightness, like a wire inside of my head and neck. Then the pain matured. It evolved. It traveled. It roamed.

“Do you grind your teeth at night?” the doctor asked me.

He was small and bald, and his skin was soft like a turtle’s neck when he held my arm to get the needle in.

The exam room was outfitted with equipment from the ’70s. This would be the perfect set for a doctor’s office in a high school play, I thought.

“Do you grind your teeth, Phil?” the doctor asked again as my black blood filled the vial.

“There was a time,” I said, “when I would not have worried what was going to happen to me. I would move from day to day without considering. When I was playing in the band. When I went to Los Angeles and Colombia.”

The doctor adjusted his glasses and watched my blood. “Go on.”

“Now everything worries me. I find myself screaming at my kids because they get within ten feet of the crosswalk without holding my hand. Drink and drugs do nothing for me. It’s not fun. Just dulls the pain.”

“Well, that’s common,” he said. “Nothing to worry about.”

He clipped in another vial, and we watched it fill with black blood.

“When I was playing in the band I didn’t worry. I was thin. It was easy to live then. But now I’ve gained so much weight. No one can recognize me. I can’t recognize myself.”

“That’s common as well. Nothing to worry about.”

“Like, what if you took my blood and told me I’ve had AIDS this whole time?”

“Are you concerned you have AIDS?”

“No, actually. I get tested often. To give myself something to feel good about.”

The doctor laughed, but just because I thought I was funny, then clipped in another vial.

“When I was a kid,” I said, “I wanted to be a basketball player.”

“I was a state champion point guard,” the doctor said. “In the Bronx.”

“Yeah, well, I was terrible.”

I started to feel lightheaded, so the doctor had me sit in a chair.

“If you faint, I won’t be able to catch you. You are enormous.”

“I worry I’m not being taken seriously.”

The doctor scoffed. “Taken seriously for what?”

Out the window, children ran across the playground. Cars beeped. A woman screamed out of a window high up in a building nearby. A bird landed on the sill, looked one way then the other, then sprang into the air and away. The doctor slipped the needle out of my arm. I could feel it tugging as it came out, like a hook through worm skin. I straightened up.

“There’s this dream I have…”

“Here we go,” said the doctor, arranging the black blood vials in a container.

“Just listen. In the dream, I’m back playing shows, and I am going to France to play a show. And there is a woman there who I am in love with. She is smart and funny, and she loves me and there is a fresh, strong desire between us. But that’s just understood. ‘On screen’ I have not seen her yet. I walk down the road in Paris and the roads are clogged with cement barriers and I am drinking a beer of some sort. I go to the club and there are a lot of people there. I make my way backstage and peek through the curtains. In the back of the room, a light comes down, a spotlight, on this woman. She waves. I take another drink and step out onto the stage, but I am suddenly so drunk I can hardly do anything. I slug through a song but the crowd boos and throws things on the stage. I fall down. When I get up the stage is empty. I go outside and it is morning. I walk to her house. I know where it is somehow. It’s an overcast day. Gray and rainy and my flight leaves in just a few hours. I was supposed to spend time with this woman. We desired each other. I get to the sidewalk outside her house and she’s inside. She is standing on her porch on the other side of a screen door, holding a cup of tea, crying. I wave and wave, but she doesn’t even notice me. She is so hurt she doesn’t recognize me anymore.”

The doctor said, “Oh brother,” and sat in a chair across from me.

Sirens wailed in the distance. I rubbed my arm where the needle was. The doctor held the container with blood vials in his lap. We both looked down. If I had cancer, I would just have to deal with it. If I had a brain tumor, I would just have to go on like that. The doctor turned the container of blood gently in his hand, like a magic orb.

“Well, Doc,” I said, “what’s it say?”

PHIL EARLE’s writing has been published in Fence, Beloit, Juked, Farewell Transmission, Barstow, Grand, and elsewhere. He edits at Post Road.

Adelaide Faith

THE CURE

Tommy says, “Oh no.” He’s looking at my hands, he’s looking at the cake. It’s chocolate, crowned with sweets. There’re jellied hearts around the edge, some are white, some are red side-up. This is how I’d spent the day: I’d made the cake and watched it cool. I’d drawn lines around my eyes and waited in bed for the sky to get dark. Then I’d headed over to Tommy’s.

When he lets me in, lasers go directly from his eyes into mine. They’re neon yellow and only slightly weaker than when we were going out. I follow him up the stairs, both of us like rabbits. In his flat, there are candles, and four people I don’t know. Because they aren’t sitting together and because each has one corner of the room, I guess they’ve taken drugs.

When I look for where to sit, I think of noughts and crosses, how there’s no way for me to win. I sit on a cushion in the center, though it’s too late to sit in the center to do me any good. I watch when someone comes out of their corner to look at the cake. They cock their head and Tommy nods and smiles. I lay back on the cushion. I close my eyes slowly, quit while I’m ahead. I’m warm, and I can hear my heart, but I can’t tell if I’m breathing.

In the silence between two songs, I think I hear Tommy say my name. I keep my eyes closed and pretend I’m sleeping before my night shift. I pretend I grew up with the Muppets and never cared what people thought, just sat up and took what I wanted. I’m in my best outfit: black jeans, grey long-sleeve my bloody valentine t-shirt, brown cardigan with chewed up cuffs. Even so, I like to imagine a floral dress—the ideal dress from every dress I’ve ever seen in real life and in films. There’s a wardrobe in my mind and it’s in there, on a hanger.

I feel the breeze of someone passing. A hand touches my hair, maybe Tommy’s, maybe not. My eyes stay shut, but I shift on the cushion, start to rub my nose. I’m going to ask for a piece of cake before I leave here for my night shift. I want to watch someone wrap it up. It feels so good to be back that I think maybe I have been asleep—for a short while at least. If I can’t work out what to say when I wake, I can just say what I see. Dinosaur, hat stand, guitar, cake, spoon. I think about the dress: Could I really pull it off?

When everything was new, I’d seen the dealer on the train and pretended not to know him. He’d moved up and down the aisle, acting like a menace. I heard later that he’d gone straight to Tommy’s and talked about which angle I looked good from, and which angle I looked bad from.

I think I hear kissing sounds and my eyes flicker open. A girl in the back corner is making the sounds but she’s not making them with Tommy. I rub my knee—there’s something there and I try to peel it off. It’s a sticker of a cherry—half is on my knee and half is on the cushion. I know it when someone changes the song. It’s the one Tommy told me he’d choose if he went on Stars in Their Eyes. He’s coming over, laughing. I’m only halfway up when he arrives. I put my arms around his legs. Then he lifts me up: dream baby, dream baby, dream baby, dream baby. First, I’m at a bad angle, then he lifts me higher, kisses my knee at the sticker.

When he gets out a knife to cut the cake, everyone looks up. He says: Would anyone want it? I steady myself on the counter and look around. One girl and three boys. I wonder what I’ll tell my best friend later. I’m glad I made it back to the room, but I don’t know how long I can keep this up. I picture myself in the dress again, and maybe my friend will want to also get one.

The first time I came to this room, Tommy had me sit on his lap, and in the silence between two songs, I’d started crying. It was the time of my life when I never knew what to do. I felt dizzy from balancing on something so small and unsteady, looking down and around at the void. Tommy told me straight away that he understood, and he said he knew the cure. Sometimes Tommy went back to his parents’ place on the weekend. They’d bring him three cheeseburgers for breakfast, separate ones, wrapped, right to his room. He’d eat them in bed, naked, without getting washed first. But it wasn’t that—that wasn’t the cure—it was the way he brushed his teeth. He told me he’d take a good long look in the mirror when he brushed his teeth and think about how good he looked. He thought he could be Perry Farrell. He looked so good, alive, his eyes so near to his brain, brushing his teeth in the morning, right in front of the mirror. It’s like he really could be anyone. And he said that was the answer, he said that was the cure, he said it was that simple, with me on his knee in that room.

ADELAIDE FAITH is a vet nurse from London. Her stories appear online at Forever, Vol 1. Brooklyn, Farewell Transmission, Hobart, Expat Press, and Maudlin House. She wrote a novel, Happiness Forever (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2025), and lives in Hastings with her daughter and dog.

Jenna Farhat

INTERVIEW WITH THE GHOST OF STEVE IRWIN

I met The Ghost of Steve Irwin in a bar one Wednesday afternoon. Like the good ol’ days, he wore his famous green cargo shorts and a pair of eyes, and his hair was arranged like pale grass. I found out he was visiting Las Vegas to make an appearance at the International Conference on Human-Crocodile Conflict. If you asked whether I saw him enter the bar I would say no, to tell you the truth, and I might clarify that ghosts are not usually subject to the limitations of a door. Taken by vodka-and-waters-with-lime and weary of The Strip’s dreadful topiary, The Ghost of Steve Irwin invited me back to the hotel where he was staying, in many, many rooms. He asked if I was willing to drive, as he could not bear to wander undetected through one more monstrous intersection, and I am always willing to drive. While walking to the car, we talked and talked. He talked like this: Crocodiles are mostly black, not green like you might think, and unlike other nocturnal reptiles, Conan O’Brien has never made me laugh because he isn’t funny. I talked like this: Kansas is actually shrinking in more ways than one, and did you know my best friend’s dad is a prairie grasses expert, and I don’t even care where my summer went? We paid a visit to my car where the sun was still hungry for metal. In my passenger seat, The Ghost of Steve Irwin could tell I was nervous. To alleviate this, he reached into his pocket for a deck of cards, a Tootsie Roll, and a McDonald’s Apple Pie, which unfolds into a kind of playing card. Ghosts famously have no need to eat, but Steve still went through the motions, and I believed him. He fanned the cards out on the dashboard. Pick a card, and I did. He reached behind my ear—is this your summer? No, I said, and I don’t care, and please don’t try to find it. He said he usually gleans nothing from his visits to Las Vegas and they are never refreshing, and he still loves his dad, the herpetologist, more than anybody else. The ignition churned and churned but the car would not start. Las Vegas was occurring all around The Ghost of Steve Irwin and I, and to us. Attempting to lighten the mood, he changed the subject to the mechanics of ghost shit, which is what Tootsie Rolls actually are. Believe me, every Tootsie Roll contains trace amounts of the very first Tootsie Roll, I said. Convinced, The Ghost of Steve Irwin reached behind my ear.

THERE WILL BE NO CRYING ON MY BIRTHDAY

A thrush will do the mockingbird thing,

I didn’t hear repetition: the sort of thing you say

on our walks. Kansas life is a borrowed thing but in April

our friends emerge and we go to bars

again, guiding each other out

by hands cupped on elbows,

around the nestling fated to the sidewalk.

A dog runs out in front of my car, stopping to lick himself

on the way home from a night

with you. Next morning

the same dog pissing against my fence.

I don’t know where life keeps coming from

or what I thought of anyone else.

My earring slips into your mouth,

silver spit on your tongue.

JENNA FARHAT, a poet and journalist from Wichita, Kansas, is working toward an MFA in poetry at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Alannah Guevara

SHATTER

Pickup truck window meets a baseball bat crack in the complex parking lot like crowded visions of carpet bomb installations, destructive via natural proclivity and a hearty inclination to defer all damage—a readymade template for the taking?

A generation of young minds is eager to live and learn and grow some into trees, some into worlds, the remaining become hands to prod and finger as spiders into crevice as gospel into guilt into a baseball bat’s loaded barrel charity/physical sensation—is any feeling comparable, every shatter a snowflake?

WHAT SECRETS WILL MY FINGERS SHARE?

Will they trickle down your back with whispers of the love you’ve scorned?

Will they braid a rat nest into your hair and dot your crown with bloodied bows?

Will they tremble under the weight of your tongue as they fumble to force you to swallow the fresh dirt from my nails?

Will they knead at the doughy fat of your demon and trace its name into your breast?

Will they chance upon unsightly blemish, caress the swollen clog of your regret, and squeeze out the spiral filth while sending pain receptors into bouts of piggish squeals?

Will they tweeze at thick hairs spared by your razor and press half-truths into the empty follicles?

Will they use hangnails to slice into your sleeping abdomen and excise the guts from your spirit?

Will they connect-the-dot your freckles into the shape of our shame?

Will they seek out the folds of your skin, slip in envelopes containing messy handwritten clues that will lead you down my history and into the unceremonious cemetery of my heart?

ALANNAH GUEVARA, “poet-wife and vilomah,” is Editor-in-Chief of Hunter’s Affects. Her work has appeared at fifth wheel press, Bizarre Publishing House, Querencia Quarterly, and A Thin Slice of Anxiety.

ABOUT THE GUEST EDITOR

TROY JAMES WEAVER wrote Visions (Broken River, 2015), Witchita Stories (Future Tense, 2015), Marigold (King Shot, 2016), Temporal (Disorder Press, 2018), and Selected Stories (Apocalypse Party, 2020). He lives in Wichita, Kansas, with his wife and dogs.

VLAD MAG #4 (PART TWO): “AND HARMONY”

VLAD MAG #4 (PART TWO): “AND HARMONY” OUT NOW!

Contributors: Joshua Hebburn, Graham Irvin, Corey Lof, Michael McSweeney, Crow Jonah Norlander, Ryan Ridge, Zac Smith, Don Television, MD Wheatley

THANKS FOR READING!

Copyright © 2026 House of Vlad Press - All Rights Reserved.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.